A team of worldwide researchers including engineers from the University of Utah have received a $9.7 million grant to design and develop a new implantable device and surgical procedure for the deaf that hopefully will cut through the noise and produce much more detailed sound than traditional hearing-loss treatments.{mprestriction ids="1,3"}

The new procedure involves the use of a new version of the Utah Electrode Array architecture, a brain-computer interface originally developed by University of Utah biomedical engineering professor emeritus Richard Normann that can send and receive electrical impulses from the brain. The version used in the new study is a special variant of the Utah Slanted Electrode Array designed for use in peripheral nerves. Versions of the Utah Electrode Array are being further developed to allow amputees to move prosthetic limbs with their mind and, in this case, to hear higher-resolution sounds than with regular cochlear implants.

Since the mid-1980s, cochlear implants have been used to treat hundreds of thousands of deaf patients. It uses a tiny device implanted in the cochlea — a spiral cavity of the inner ear that produces nerve impulses from sound vibrations — to stimulate the auditory nerve. But the implants don’t work for everyone because of some patients’ anatomy or other malformations. And for those in which it does work, the sounds they hear may not be detailed, preventing them from distinguishing music or understanding voices in a noisy room, for example.

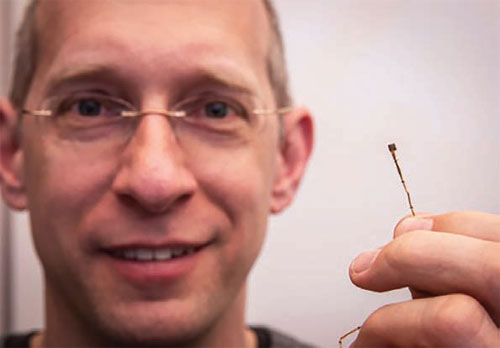

The new procedure, which is being funded by a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health, could help those who are normally not candidates for cochlear implants, said University of Utah electrical and computer engineering professor Florian Solzbacher. That’s because the Utah Electrode Array assembly, a small (1.2mm x 1.8 mm) silicon chip attached to a bundle of wires and connected to a stimulator device, is implanted directly to the patient’s auditory nerve as opposed to the cochlea.

“You have much higher resolution of sound, which means you can cover more individual frequencies and have better tonal range,” said Solzbacher, who is the lead UofU researcher working on the team. “That should allow you to get more realistic hearing.”

Another benefit of this technology is that the electrode array could be connected to existing hearing aids normally used in regular cochlear implants and does not require specially designed devices. As a clinical product, the implanted array must be designed to last about 30 years in the body.

During the first three years of the grant, the team will develop the technology and surgical procedure and ensure it is safe and effective. The final two years will be devoted to implanting the devices on three patients with hearing loss who are normally not candidates for cochlear implants.

The team will be led by researchers from the University of Minnesota and includes scientists from The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, the research branch of Northwell Health, headquartered in Manhasset, New York; Hannover Medical School, a university medical center in Hannover, Germany; International Neuroscience Institute in Hannover, Germany; Hannover Clinical Trial Center in Germany; Salt Lake City-based Blackrock Microsystems LLC, an implantable neurotechnology device company that has been developing the Utah Electrode Array; and MED-EL, an Austrian manufacturer of medical devices for hearing loss.

Normann’s Utah Electrode Array, which he began developing in the 1980s, has also been used in a variety of research including for pain modulation, the development of a bionic eye that can help the blind see again, for bladder control, to regulate epilepsy and even for neural disorders such as Alzheimer’s.{/mprestriction}