Robert Spendlove

The labor market continues to be a puzzle. The unemployment rate is back to where it was before the pandemic and the number of jobs created is much higher than analysts expected. However, we still struggle to bring people off the sidelines and back into the labor force. Shouldn’t a strong economy entice more people to work?

This is one of the challenges the Federal Reserve faces as it tries to bring the economy back to normal. The Fed is targeting “below-trend” growth in the economy to cool things back down after several years of overheating. But in doing so, the Fed runs the risk of pushing it into a recession.

Inflation is down significantly compared to{mprestriction ids="1,3"} last year, but price increases remain too high. While supply chains are largely back to normal, some sectors are seeing “sticky” price increases that are struggling to come down. This includes the service sector, where price hikes are primarily driven by wage increases rather than input prices. So, when the Fed says they want below-trend growth, what they mean is they need the labor market to slow.

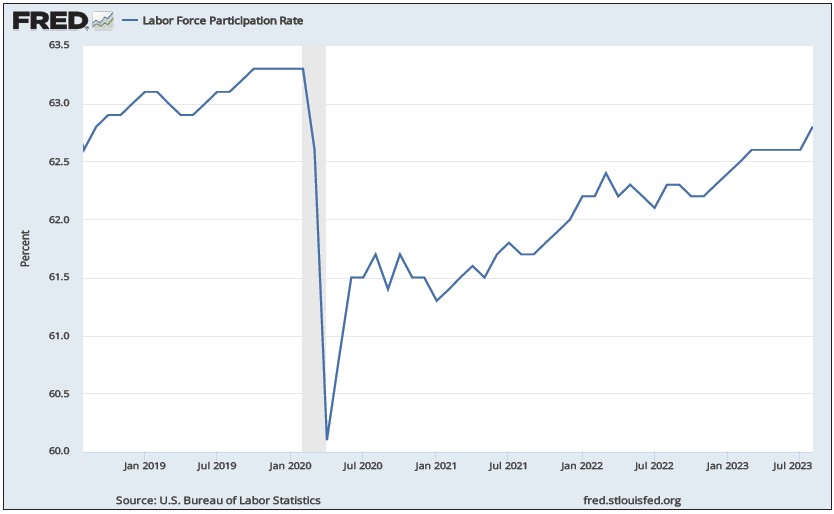

One of the main measures of labor market strength is the labor force participation rate, which measures the pool of potential workers available in the economy.

The U.S. labor force participation rate peaked in 2000 at 67.3 percent. Since then, it has been gradually trending lower, dropping to 63.3 percent in early 2020 as baby boomers reached retirement age and left the labor force. This “silver tsunami” of retiring boomers wasn’t a surprise, but the COVID pandemic caused the wave to crash.

The U.S. labor force participation rate peaked in 2000 at 67.3 percent. Since then, it has been gradually trending lower, dropping to 63.3 percent in early 2020 as baby boomers reached retirement age and left the labor force. This “silver tsunami” of retiring boomers wasn’t a surprise, but the COVID pandemic caused the wave to crash.

In two months, from February to April 2020, the participation rate dropped to 60.1 percent, as 22 million people lost their jobs during the outbreak of COVID. Since the pandemic, the participation rate has been slowly increasing as groups of people return to the workforce. But the rate currently only stands at around 62.6 percent, and it hasn’t increased in four months. This gap in labor participation represents millions of people who haven’t come back off the sidelines to return to the workforce.

Different groups have had unique reactions to the pandemic economic shocks. The labor force participation of “prime age” workers, who are between 25 and 54 years, old dropped initially in 2020 but has since fully recovered and is now higher than before the start of the pandemic. However, the labor participation rate of workers 55 years and older is still far below levels from 2020. The participation rate for this age group has been trending lower for the past 18 months.

This imbalance in the labor market is one of the main targets of Federal Reserve policy actions. Since it is very difficult to increase the supply of labor and get people to come out of retirement and return to the labor force, the Fed instead is focused on reducing the demand for labor. Rising interest rates increase the cost of business borrowing, which should slow demand for workers.

However, many businesses are reluctant to let workers go and job vacancy rates remain high. It’s still too early to tell whether a soft landing is possible or whether the overheated economy will cool too quickly over the next few months. If the current labor market conditions continue, this could represent a new normal and we won’t return to pre-pandemic labor force participation. Dynamic economies like we have in the United States can adjust, but the road ahead remains foggy.

Robert Spendlove is the senior economist for Zions Bank in Salt Lake City.{/mprestriction}